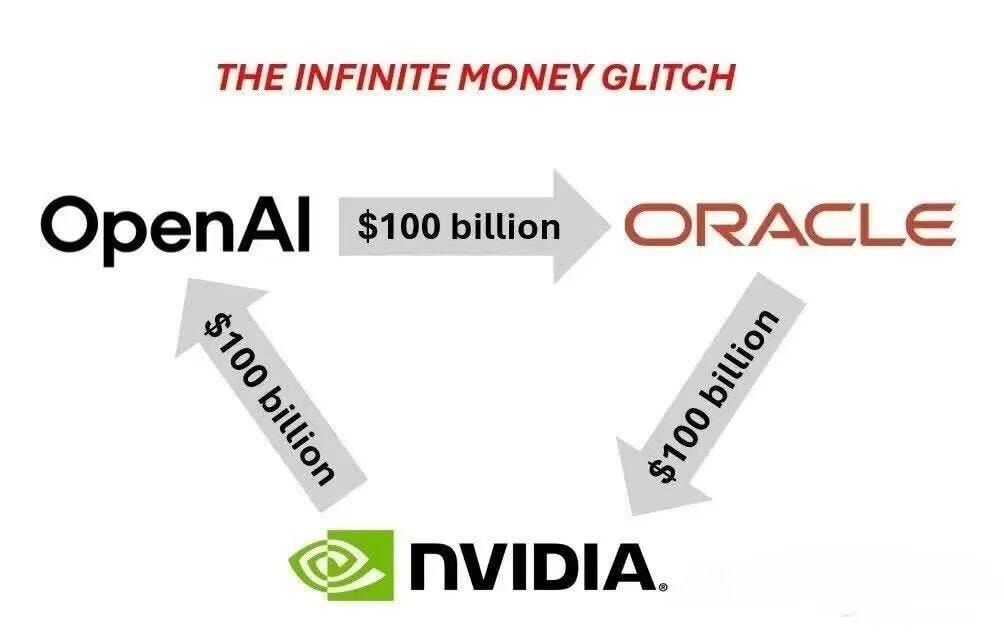

Nvidia made headlines this week when it announced it would invest up to $100 billion into OpenAI and help deploy at least 10 GW of AI infrastructure. The move, frequently memed as an “infinite money glitch,” with capital and revenue cycling between Nvidia and OpenAI (see below image), effectively ensures a substantial fraction of Nvidia’s GPUs will land in OpenAI‑aligned datacenters (via leasing or outright purchases).

This comes on the heels of OpenAI’s >$300 billion “Stargate” build‑out with Oracle, which targets ~4.5 GW of capacity, further tightening the market for top‑end accelerators.

And that’s before accounting for OpenAI’s ongoing expansion on Microsoft Azure, where the relationship now runs under a right‑of‑first‑refusal model for new capacity rather than blanket exclusivity, still conferring practical priority on Azure deployments while allowing OpenAI to add capacity with other partners.

Netting this out: through the end of the decade, OpenAI has assembled an envelope of roughly 10–15 GW of Nvidia‑powered capacity across Oracle, Microsoft, and other partners with overlap between these footprints, so think of this as a shared umbrella rather than purely additive numbers. For context, independent analyses estimate ~10 GW of additional AI data‑center power could be needed globally in 2025 alone; in other words, OpenAI’s program is on the scale of a full year of incremental world AI build‑out.

The above data implies Nvidia GPU availability will tighten substantially for other frontier‑model players—Anthropic (primarily on AWS), xAI, Meta, and Google DeepMind—raising effective prices and lead times and forcing harder choices about model cadence, context windows, and training tokens.

Google has been trying to break out of this Nvidia-dominated mold for years through the development of its own own AI‑specialized TPUs for training and inference. But these in-house designed chips still pass through chokepoints that Nvidia heavily influences, especially TSMC wafers and advanced packaging. By the end of 2025, analysts expect Nvidia to be ~20%+ of TSMC revenue (second only to Apple), and the CoWoS‑class packaging and HBM ecosystems remain binding constraints even as capacity expands. TSMC’s allocation is fundamentally contractual, driven by prepays and take‑or‑pay deals, and it will be reluctant to shift meaningful share away from Nvidia while demand remains red‑hot.

To escape the straightjacket created by the Nvidia‑OpenAI alignment, Google should buy Intel (or a substantial portion of it), fund the High‑NA EUV ramp, and prepare to manufacture TPUs on Intel fabs as that capacity comes online. That gives Google end‑to‑end control of its AI training infrastructure—chip architectures, training software, chip manufacturing, and data center buildout—and a guaranteed runway independent of Nvidia’s queue.

Recent events make this even more urgent. Nvidia just disclosed a $5 billion Intel investment at $23.28/share (roughly 5% of Intel’s outstanding shares), alongside a product pact in which Intel will build x86 SoCs integrating Nvidia RTX GPU chiplets for PCs and collaborate on custom data‑center CPUs—clear evidence that Intel’s roadmap can be steered by anchor customers. Intel is also now soliciting an Apple investment, according to Bloomberg/Reuters reporting.

Given the quickly changing dynamics around Intel, Google must act quickly and decisively. For example, a $25 billion purchase at $35/share would buy on the order of ~714 million shares, implying ~16%–17% of Intel based on ~4.37 billion shares outstanding—placing Google ahead of both the U.S. government (~10%) and Nvidia (~4–5%) as the largest shareholder. That level of ownership could anchor governance and direct capex toward TPU‑critical fabs and packaging lines.

In practice, this looks like the following:

A minority stake + board influence sufficient to align Intel Foundry’s roadmap to TPU requirements

A TPU-only supply compact: multi-year, take-or-pay wafer and advanced packaging commitments, with right-of-first-allocation during shortages and pricing bands tied to verifiable tool/packaging milestones.

Parallel open‑market TPU SKUs to keep utilization high and de‑risk capex—turning Google’s silicon into a software‑first, capacity‑priced product.

#3 is the longest shot, but perhaps the most enticing benefit of the investment. This would open up a second profit engine to fuel Google’s growth over the next decade, especially as its Search business comes under threat from AI-search competitors (such as OpenAI’s search-enabled offerings). In fact, Nvidia’s data‑center business is now running at an annualized ~$160 billion revenue pace, which is comparable to Google’s Search cash cow. Thus, the addition of the TPU revenue line provides substantial growth opportunities and a potential hedge against Google’s eroding search moat.

If this plan works, Google gets scheduling certainty, lower $/token, a faster model cadence independent of Nvidia’s allocation calendar, and another revenue stream that could potentially reach the level of Google Search. If it stumbles, the downside is capped at a financial position that should still appreciate if Intel’s foundry inflects. Either way, for $25 billion, Google can buy its way out of the Nvidia-TSMC duopoly and into the driver’s seat of AI compute.