While listening to Dwarkesh Patel’s excellent podcast with Stephen Kotkin (go listen to it if you haven’t yet. I’ll wait.), Kotkin made a very interesting point on the dynamics that led to the Communist revolutions in Russia and China. I’ll provide an excerpt below (emphasis mine):

[In Russia and China], you have this peasant land hunger. The peasants are often without their own holdings. They work on someone else's property, or their holdings are so small that if there's a little bit of bad weather let alone a massive drought, they're on the verge of starvation. Subsistence level agriculture is not politically stable…

You need to deal with the peasant land hunger so that it becomes a stabilizing political force. You have the peasants get the land and then they have a piece of the status quo and want to retain the system, versus the peasants not having the land and they want to overthrow the system to get the land…

So the peasants had their own revolution in 1917 and 1918, which was not about the socialist parties. It's not about the Bolsheviks, it's not about Lenin, it's about the peasants seizing the land. But that creates an intense radicalism that becomes the platform for the socialists in the cities to gain and hold power in the system. You don't have that in the German case.

Kotkin’s claim here is that a large, landless peasant class provides a powder keg, and the Communist movements in Russia and China were smart enough and opportunistic enough to capitalize on this latent instability in the system. By contrast, in Germany, the peasants were predominantly landowners, which provided the stability to weather the Communist movements. Meanwhile, in England, peasants as a class were starting to give way to the urban factory worker, who was able to progressively win voting rights and the right to organize into labor unions.

This result with a Red Russia & China, a fascist Germany, and a capitalist UK seems obvious in retrospect, but for an observer in pre-WWI Europe, this would actually be an extremely surprising result. It was often assumed by Communist intellectuals (including the leaders of the Communist movement) that the global Communist Revolution would begin in England and Germany, which were perceived as the ripest environments for labor to overthrow the capitalist class.

So why did these dynamics play out so counterintuitively? To understand this, let’s analyze the sociological model implicit in Kotkin’s explanation for the causes of the Russian and Chinese revolutions. Broadly, I think Kotkin’s framing of the issue rests on separating the populace into two groups

The Dampeners represent the social classes who have a stake in the prevailing order—they have this stake because they stand to gain from political and economic stability and to lose from political and economic instability. In the tsarist Russian context, this would include the tsar and his bureaucrats, as well as the large landowners.

The Powder Kegs represent the social classes who feel they do not have a stake in the prevailing order—that is, they feel they do not stand to gain from political and economic stability and, similarly, do not stand to lose from political and economic instability. In the tsarist Russian context, as we’ve discussed, this group is most easily seen in the landless peasant class.

The Dampeners, then, can be thought of as any groups that are currently benefiting and, importantly, feel as though they are benefiting from the current economic, political, and social structure. They represent the vanguard of the current society, defending its interests since the society’s interests are their interests as well. That is, their natural inclination is to dampen any dramatic oscillations in their society in order to defend their current interests and their perceived upside. The Powder Kegs, on the other hand, can be thought of as disenfranchised groups that do not have a stake in the nation’s future. Due to their lack of downside in the face of societal collapse and lack of upside if society remains stable, this class is incentivized to flip the game board over and try to start over. However, in many cases, they will remain latent without an outside spark to light the powder keg.

In this framing, we can think of the Powder Kegs as generators of civilizational tail risks.

An Explanation of Tail Risks & Non-Ergodicity

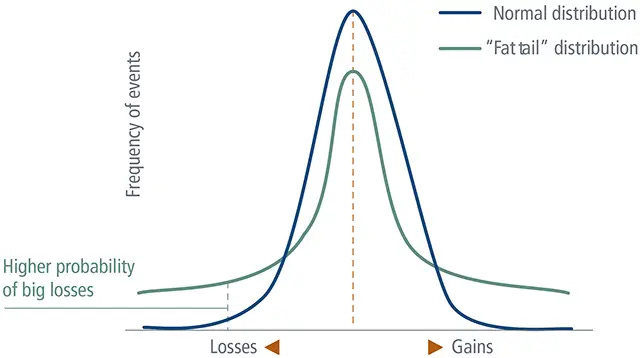

In the finance world, tail risks are low probability events that cause immense losses (i.e., the left side of the normal distribution in the above image). Tail risks in finance and many other domains also tend to have the following characteristics that make them especially pernicious:

They tend to more closely follow a fat-tailed distribution—that is, low probability events occur more often than would be expected by a standard normal distribution modeling the event (e.g., 1-day stock returns) have the following characteristics that make them especially pernicious:

The impact of the tail risk is typically much higher than the impact of a more typical data point. For example, a single day when the stock market crashed can wipe out years’ worth of gains.

Given the above, in fat-tailed domains with high-impact left-tail events, we need to be especially careful about defending against (ahem, dampening the effects of) tail risks. And society is the fat-tailed domain. As difficult as forecasting in finance is, forecasting future political and social developments using history might as well be astrology. It’s highly qualitative, subject to opinion, and, as a result, suffers from human status quo biases (or “nothing ever happens,” as the Twitterverse says). Hence, we almost definitely underestimate low probability events in human society. Thus, the distribution is fat-tailed. In addition, we know that the risk of tail events in human society is immense—just look at the Bronze Age Collapse or Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. Thus, the distribution of impactful societal events is fat-tailed with extremely high-impact tail events.

You may now be thinking, “Okay, these tail events are definitely a concern. But they are, by definition, low probability, so do we really need to worry about them?

Enter non-ergodicity.

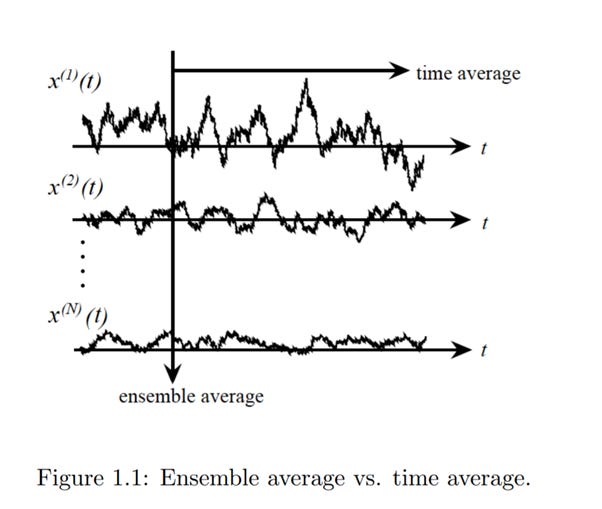

To discuss non-ergodicity, we’ll start by intuitively defining ergodicity. Let’s imagine a volume such as a box and some time-dependent process like the motion of a particle in the box. Now, suppose we take two distinct measures of the box:

We look take a particular point in time and compute the average position of all particles in the box.

We fix our attention on one particle and track its trajectory over time. We then compute the average of this one particle’s position based on the data we record as we follow it around the box

In the first measure, we are computing a spatial average—we look spatially across the box, identify the positions of all particles in it, and then find the average position of these particles.

In the second measure, we are computing a temporal average—we focus on one particle across time, identify all positions that it visits, and then compute an average of these positions.

Mathematically, we can identify the spatial average as the standard expected value of a continuous random variable that you should be used to if you’ve taken an intro course in statistics or probability:

Meanwhile, the temporal average is given by the following:

If the above two notions of an average are equal for a given random process, then we say that it is ergodic. Continuing our physical intuition, this equality is saying that, if we follow the motion of one particle in our box, it will visit all of the locations in the box in the exact proportions that we would expect to find all of the particles at a fixed time. That is, we can use spatial and temporal averages interchangeably because they are the same for ergodic processes. The particle motion example was chosen deliberately, as Brownian motion (i.e., the random motion of particles in a volume) is one of the canonical physical processes exhibiting ergodic behavior.

Now, non-ergodic processes are random processes in which the spatial average and the temporal average are not equal. The behavior of one data point over time does not equal the average behavior across all data points at one instant in time.

Why do we care to make this distinction? Because whenever people talk about averages, they almost always default to the spatial average and then go on to use these averages to make predictions about particular data points. For example, people will often say, “The average yearly return for the S&P 500 is 10%, and therefore I can model my portfolio as gaining 10% per year.” I hope now the issue with this thinking is clear: our hypothetical stock allocator has computed a spatial average and then applied it to one data point over time without checking if the process is ergodic! And, spoiler alert, stock returns are a canonical example of non-ergodic processes, so this reasoning would lead to dangerously faulty conclusions!

Let’s now explore exactly why the combination of underestimating tail risks and confusing ergodic and non-ergodic processes is so dangerous with a concrete example.

Tail Risks, Non-Ergodicity, & Society

We’ll start by building a simple model of the real GDP growth of a standard developed economy that has a latent probability of collapse. We can model this as a discrete-time process, where each year is treated as a single period. In any given year, we will estimate a 0.1% chance of ruin (i.e., the hypothetical country fails and its real GDP goes to 0). This can represent governmental collapse, nuclear war, incurable diseases that wipe out the population, etc. In the vast majority of years (with a probability of 99.9%), we’ll forecast that the country’s real GDP growth is normally distributed with a mean gain of 2.5% and a standard deviation of 0.5 percentage points.

This setup combines the main concepts of tail risks and non-ergodicity that we mentioned previously:

Tail risks — we have a 0.1% chance of ruin in any given year. So our risk is extremely rare but also very impactful, just as we’ve defined tail risks.

Non-ergodicity — when a country fails (i.e., its GDP goes to 0), it doesn’t have the chance to start over. Hence, if we follow the failed country over time, after it fails, it doesn’t have the chance to explore the full state space (and hence the temporal average will differ from the spatial average).

These two effects, when combined, produce very shocking effects, even though at first glance it might look like we only have a 0.1% chance of catastrophe.

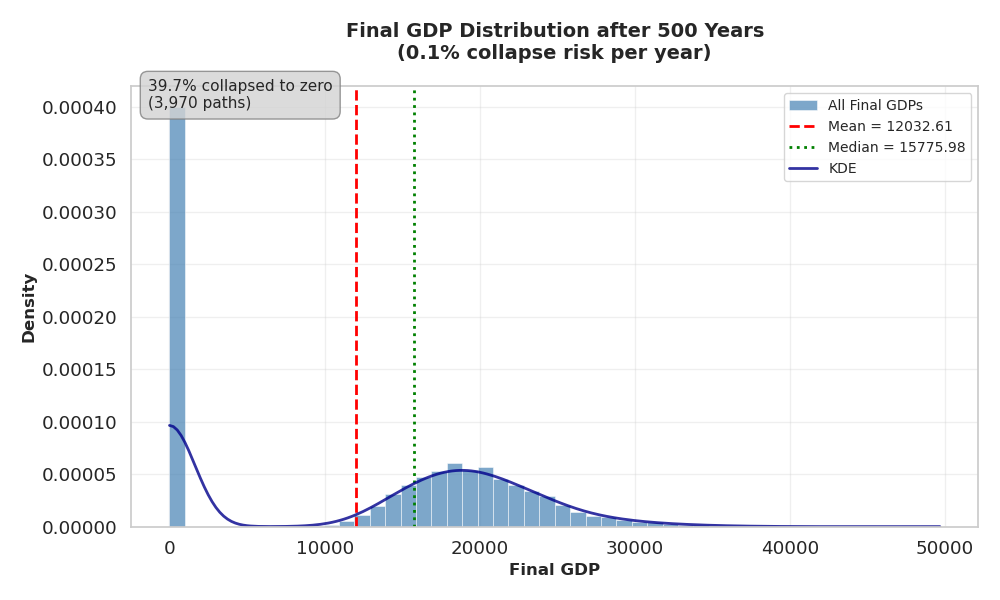

We’ll now run this simulation for 500 years and observe the effects. In this simulation, every country will start with a GDP of $1.

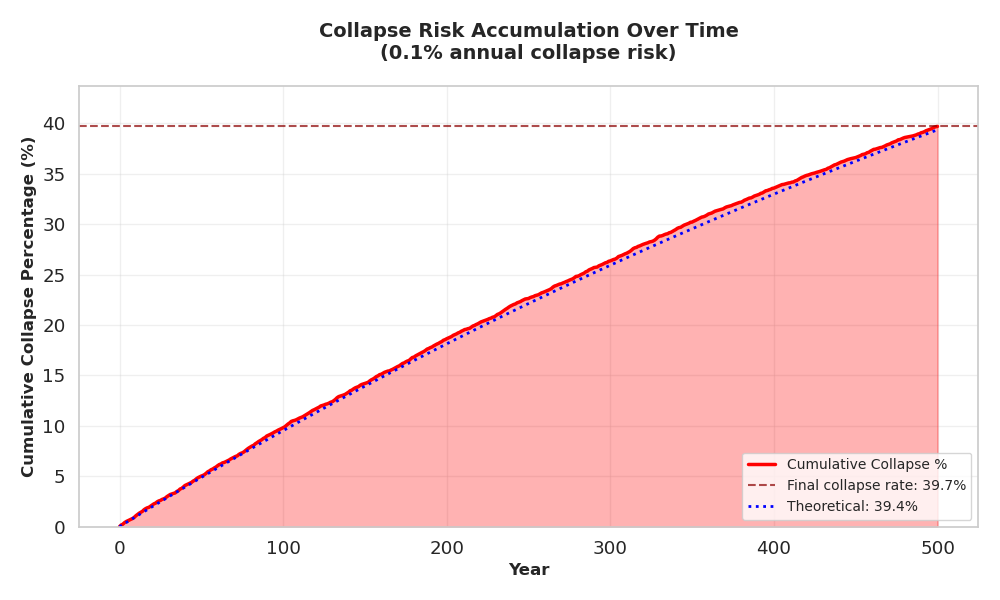

I want to start by directing your attention to the left side of the graph. You’ll see that a full 39.7% of countries in this simulation collapsed, with their GDPs going to 0. Our initial intuition that we had a 0.1% chance of catastrophe was incredibly wrong—we have a 0.1% chance of catastrophe in any given year, but the chance that society fails in any year increases as time advances! Rather than saying “we have a 0.1% chance of catastrophe”, which sounds relatively benign and pushes people towards complacency, it would be far more accurate to say “we have a 40% chance of catastrophe in the next 500 years”, which sounds much more dire.

Now, take a look at the legend in the top-right corner of the graph. Here, you can consider the mean to be the spatial average we’ve been discussing—hence, in the vast majority of conversations where this data is getting discussed, someone would likely say “the average country over this 500-year sample saw its GDP grow from $1 to $12,032.61, a gain of 1,203,160%”. Hence, the reported “average”, the spatial average, actually doesn’t capture the experience of living in these conditions at all! You would think, based on seeing an average gain of over 1 million percent, that all or most countries developing under these conditions would be on the march to utopia. However, these countries only have barely better than a coin flip’s chance of not collapsing into complete chaos in this 500-year sample!

To better understand the dynamics of this process, we need to instead look at the temporal average. We can do this by computing the geometric mean of returns for each individual path and then averaging this set of geometric returns. This yields an average yearly loss of 39.5%, with an expected ending value of $0, aligning much more closely with the collapse dynamics we see in the histogram. This brings us to an even broader insight that can be made here, which we can see in the plot below.

As time moves forward in our sample, more and more of the countries are collapsing. Taking this to the limit, eventually, all societies in this simulation will collapse. Even more generally, when the probability of catastrophic ruin is greater than 0, any society will collapse given enough time.

To tie things back into the beginning of our discussion, what Kotkin has identified in his analysis of the latent instability in the 20th-century Russian and Chinese societies is that the presence of disenfranchised peasant groups increased the yearly chance of ruin for these societies, and thus led to their demises. Combining with our analyses above, we see that when one or more Powder Keg groups exist in a society (making the probability of ruin non-zero), the long-run survival probability of that civilization is exactly 0. The more such Powder Kegs exist, and the more groups that appeal to these groups, the greater the probability of collapse in a given year.

On the flip side, if we re-run the simulation with an order of magnitude lower probability of ruin (i.e., a 0.01% risk of collapse per year), we see a huge reduction in risk in the 500-year window. Only 4.7% of societies in this scenario collapse, reducing our risk of ruin by 35 percentage points.

Given these analyses and the conclusions we’ve drawn, it would seem that identifying potential Powder Kegs and implementing policies to let off some steam are some of the most important actions a government can undertake. If we can identify these groups and pacify them, we can substantially improve the survival probability of our society over large timescales and avoid outright collapse. The late Russian tsars and Chinese emperors failed to identify and pacify their Powder Keg group. The Communist parties in those countries, however, did not overlook the peasant Powder Keg group and were thus able to leverage them to bring the country’s risk of ruin to reality.

With this lesson in mind, let’s look at a Powder Keg group that is roughly analogous to the landless peasants in tsarist Russia and examine some ways we can defuse the impending explosion.

A 21st Century Powder Keg & Its Potential Solutions

To identify our Powder Keg, let’s return to our definition of the group: we need to find a social class that doesn’t have a stake in the prevailing political order. That is, we need to find a group that doesn’t stand to gain from the country’s success since it doesn’t own a stake in the country, and also has the subjective feeling that it will never achieve such a stake in the current system. Hmm… where can we find such a group?

If you clicked on any of the myriad links in the previous paragraph, I think it’s clear that Gen Z fits the bill—they are currently dealing with extremely high housing costs that have put home ownership out of reach for many members of that generation (at least, that is, in the cities with the jobs they’d want to work and places they’d want to live). Most importantly, this generation feels like it will never get better. There is a very strong, pervasive sense that society is fundamentally set up so that they won’t succeed. We can see this dynamic starting to play out politically, with Gen Z shifting strongly to Trump during the presidential election, who openly espoused the need to tear down the current economic and social order to “Make America Great Again”. We are also seeing this in New York City, where Gen Z voters are turning out in strong numbers to vote for Zohran Mamdani, the once‑underdog‑turned‑favorite mayoral candidate who has some fairly openly held anti-capitalist views.

Whether or not the issues Gen Z faces require a radical overthrow of the prevailing social order, much of Gen Z certainly feels that this is the case. And that is enough for a radical group (like the Communists did in 20th-century Russia and China) to leverage this group as the bedrock for a revolution. Which means, to protect our civilization from collapse, we have to resolve the issues they’re facing and give them (and future generations) a stake in the current social order.

The way I see it, having a stake in American society as it’s currently constructed essentially amounts to two things:

Owning a home

Owning a piece of the stock market

Owning a home is the traditional view of success in the United States, and so the inability to buy causes immense stress to younger generations. It makes them feel shut out from the typical path to prosperity that their parents and grandparents have followed. And, as we’ve discussed, simply feeling that there is no hope is enough to provide a latent layer of unrest, regardless of its truth. By providing them with a pathway to home ownership, we could reduce the anxiety and anger directed at the US social order. In addition, home ownership typically connects people to a community more than renting does, as they can form more permanent roots, which could also help to assuage the social isolation felt by many in the younger generations.

Similarly, the more modern view of success amounts to having significant capital in the US stock market. Gen Z generally feels resentment towards US companies and CEOs, mostly because they feel that they are being “robbed” or taken advantage of by these companies. This feeling is likely augmented due to their lack of ownership in the stock market—if they owned a slice of all of these corporations, it would be much harder to feel robbed since Gen Z would, in turn, be getting richer from their success.

So we now have a two-pronged approach—give young people a vested interest in US corporations and a vested interest in the housing market. Both of these assets will reduce the desire for societal disruption and instead incentivize stability and growth, since younger people would now be directly harmed by disruption and directly benefit from growth.

What would policies targeting these two areas look like?

Housing Policy

To defuse the Gen Z Powder Keg through housing, we must confront the sacred cows of American urban planning and economic policy head-on, adopting measures that prioritize radical supply-side interventions over the palliative demand-side subsidies that have only inflated bubbles and entrenched resentment. The goal here is not mere affordability tweaks but a structural overhaul that floods the market with housing units, crashing prices to levels where ownership becomes a default expectation rather than a distant dream, thereby converting potential revolutionaries into vested stakeholders who crave stability to protect their newfound equity.

First, deregulation stands as the linchpin: easing zoning laws, building codes, and permitting processes to unleash denser, faster development. In cities like San Francisco or New York, where Byzantine zoning ordinances have artificially constricted supply, we could emulate the Houston model on steroids. Imagine upzoning entire neighborhoods to allow mid-rise apartments and mixed-use developments without the endless environmental impact studies or community vetoes that currently serve as de facto barriers erected by incumbent homeowners (our modern Dampeners) to preserve their scarcity-driven windfalls. By slashing approval timelines from years to months, we'd not only multiply housing stock exponentially but also incentivize innovation in modular construction and prefabrication, driving down costs through economies of scale. This isn't about anarchic sprawl; it's about recognizing that the current regulatory thicket is a form of crony capitalism, protecting legacy interests at the expense of intergenerational equity. The contrarian insight? Such deregulation would disproportionately benefit high-density urban cores, where Gen Z wants to live, fostering vibrant, walkable communities that counteract social atomization, turning isolated renters into networked homeowners with skin in the civic game.

Complementing this, implement a land value tax (LVT) while eliminating traditional property taxes. Drawing from Georgist economics an LVT taxes the unimproved value of land itself, not the structures or improvements upon it. This shifts the fiscal burden onto speculative land hoarders and absentee owners, who currently profit from scarcity without contributing to productivity, and rewards those who build densely and efficiently. In practice, this would discourage vacant lots in prime areas (a plague in places like Los Angeles) and encourage vertical development, as the tax incentivizes maximizing output per square foot. Eliminating property taxes, which penalize improvements, removes the disincentive to renovate or expand, further accelerating supply. The net effect? Housing prices plummet as land speculation collapses, making entry-level ownership feasible even for baristas or entry-level coders. Critically, this policy is revenue-neutral or even positive for governments, funding infrastructure without the distortionary effects of income or sales taxes.

Next, a targeted reduction in union power within the construction sector to slash labor input costs. Unions, while historically vital for worker protections, have in many blue states metastasized into rent-seeking guilds that inflate wages far above market rates through prevailing wage laws and project labor agreements, adding 20-30% premiums to public projects alone. By reforming or outright repealing these mandates (perhaps via federal preemption in interstate commerce-affected builds), we could introduce competitive bidding from non-union labor, including skilled immigrants under expanded visa programs. This isn't anti-labor animus; it's a recognition that artificially high costs perpetuate the very inequality unions purport to fight, locking out younger workers from affordable homes while padding the pensions of Boomer incumbents. The result? Faster builds at lower prices, with spillover effects into related industries. Tie this to broader labor market fluidity (e.g., right-to-work expansions) and we create a virtuous cycle where construction booms absorb underemployed Gen Z, giving them immediate income upside alongside future ownership stakes.

Finally, ramp up domestic energy production to crater energy input costs, which permeate every stage of housing development from raw materials extraction to HVAC installation. Fracking, nuclear deregulation (streamlining NRC approvals to Yucca Mountain levels of efficiency), and offshore drilling expansions could flood the market with cheap BTUs, reversing the green energy mandates that have jacked up costs via intermittent renewables and grid unreliability. By prioritizing baseload abundance we not only halve construction energy bills but also enable all-electric homes that are cheaper to operate, further lowering the ownership threshold. In our tail risk framework, this policy acts as a multiplier: cheaper energy stabilizes the broader economy, reducing the probability of ruin from exogenous shocks like oil crises, while directly empowering the housing supply surge that integrates Gen Z as Dampeners.

Implemented holistically, these policies could halve median home prices in high-demand areas within a decade, per supply elasticity models, transforming Gen Z's latent rage into conservative impulses. After all, nothing quells revolutionary fervor like a mortgage and rising property values.

Stock Market Policy

Shifting to the equity side, the objective is to forge a direct umbilical cord between young Americans and the productive engine of capitalism: the stock market. Rather than the anemic 401(k) matches or tax-advantaged IRAs that presuppose stable employment and disposable income, we need audacious, universal mechanisms that inject ownership stakes from cradle to career, preempting the feeling of disenfranchisement that fuels Powder Kegs.

The recently enacted MAGA (Money Accounts for Growth and Advancement) accounts (rebranded as Trump Accounts in the final text of the One Big Beautiful Bill) represent a strong starting point in this. These accounts automatically seed every eligible newborn with a $1,000 federal contribution (under a pilot for births from 2024 to 2028), invested in diversified funds tracking U.S. equity indices like the S&P 500, with tax-advantaged growth and additional contributions capped at $5,000 annually from taxable entities or unlimited from tax-exempt organizations. Access is tiered—no withdrawals until age 18, then partial for qualified purposes like education, entrepreneurship, or homebuying, expanding at 25 and fully unrestricted at 30—with favorable long-term capital gains taxation on qualified distributions. These accounts instill from infancy a visceral sense of ownership in corporate America, equating personal gain to national prosperity. To secure broader political alignment and ensure the program's longevity beyond electoral cycles, however, a further rebranding is essential, shedding the partisan connotations of "MAGA" or "Trump Accounts" in favor of a neutral, inclusive name like "American Future Funds" or "National Prosperity Accounts." This move transcends left-right divides, framing the initiative as a non-ideological investment in collective stability; by inviting buy-in from all societal factions, we mitigate the risk of future repeals or sabotage, transforming it into an enduring institution that unites rather than polarizes, much like Social Security evolved from its contentious origins into a bipartisan bedrock.

However, these accounts don’t go far enough: the $1,000 seed is paltry in the face of compounding's long horizons (barely scratching $10,000 by age 18 at historical 7% real returns), eligibility skews toward newborns and young children (leaving Gen Z and millennials largely sidelined without retroactive catch-ups), contribution limits throttle broader participation, and the delayed access risks alienating a generation already primed for immediate disruption over deferred gratification. To truly dampen tail risks, we must expand them aggressively: scale the initial deposit to $5,000, extend automatic enrollment with catch-up lumps ($10,000+) for 18-35-year-olds funded by reallocating corporate tax windfalls from buybacks to "citizen shares," eliminate age-based restrictions in favor of penalty-enforced long-term holds, and broaden investment mandates to include total-market ETFs for true diversification. This supercharged version subverts the Marxist narrative of "exploitation by capitalists" by making everyone a micro-capitalist, diluting class warfare into shared prosperity. In tail risk terms, widespread equity ownership dampens systemic shocks; if a critical mass holds stakes, political pressures shift from "eat the rich" to "protect the market," reducing the annual ruin odds by fostering a Dampener supermajority.

To amplify this foundation even further, redirect any universal basic income (UBI) pilots or proposals straight into mandatory stock purchases for recipients under an expanded "Universal Basic Equity" (UBEI) framework, rather than cash disbursements that dissipate into consumption traps. Imagine channeling equivalent funds (say, $1,000 monthly equivalents) into the augmented MAGA/Trump Accounts or similar diversified portfolios, perhaps via Vanguard-esque vehicles with algorithmic rebalancing. This forces skin-in-the-game; recipients become vested in corporate efficiency and innovation, as their "income" derives from dividends and appreciation rather than zero-sum transfers.

Collectively, these stock policies embed a profound incentive alignment: young people gain from US economic ascendance, viewing disruptions—like tariffs or regulations—as direct threats to their wealth. This vested interest in continued success transmutes Powder Kegs into Dampeners, slashing civilizational ruin probabilities and extending our society's survival horizon indefinitely.

Conclusion

In revisiting Kotkin's insights on the peasant-driven upheavals that toppled empires in Russia and China, we've unearthed a timeless sociological truth: societies teeter on the edge of ruin when disenfranchised masses, our Powder Kegs, accumulate without recourse, their latent volatility amplified by opportunistic sparks. Through the lens of tail risks and non-ergodicity, we've modeled this as an inexorable march toward collapse in any system where the annual probability of catastrophe exceeds zero, where spatial averages seduce us into complacency while temporal realities reveal the fragility of civilizational paths. Gen Z, as the 21st-century analog to those landless peasants, embodies this threat not through malice but through a profound sense of exclusion from the American dream's twin pillars: homeownership and equity participation.

The policies outlined—radical housing deregulation paired with Georgist taxation, union reforms, and energy abundance to crash barriers to entry; alongside expansions of rebranded, universal stock accounts and equity-directed UBI to democratize capital—are strategic dampeners designed to integrate the alienated into the status quo's vanguard. By granting tangible stakes in stability, we slash that ruin probability, extending our society's viable horizon from inevitable doom to indefinite prosperity. This represents a first attempt at pragmatic ergodic engineering: in a fat-tailed world, the true revolutionaries are those who preempt the keg's ignition, ensuring that history's surprises favor continuity over cataclysm. Ignore this at our peril; embrace it, and we might just forge history’s first immortal civilization.