Open Source LLMs Are Eating the World

Closed source models solve tasks first. Open source models make them cheap.

The default way we evaluate large language models is fundamentally misaligned with how they create economic value. We track frontier capabilities across broad benchmarks (such as ARC-AGI-2, FrontierMath, and SWE-Bench Verified) and implicitly assume that whoever leads on these metrics captures the most value.

However, this view assumes that what matters is the model’s maximum intelligence acorss a broad range of tasks — the “PhD intelligence for all” mantra repeated by the large labs.

For practical company building, this framing is wrong, and understanding why reveals a structural advantage for open source models that holds regardless of when (or whether) we achieve AGI.

I. Introduction: The Benchmarking Problem

The standard narrative goes something like this: general model value scales with general performance. A model that scores higher on a diverse battery of benchmarks is more valuable than one that scores lower, and the companies training the most capable models will capture the lion’s share of economic returns.

But this misses how value actually gets created in practice. Companies don’t build products that require uniformly excellent performance across all possible tasks. They build for specific use cases: contract analysis, customer support, code generation, medical documentation. Revenue comes from solving customer problems, and customer problems are specific. The “average” benchmark performance that frontier labs optimize for doesn’t map to any real product, it’s just an abstraction that obscures the actual economics.

For any given application, what matters is whether your model is good enough at this particular thing, not whether it can solve PhD-level mathematics problems or write publishable research. A legal tech startup needs strong performance on contract reasoning and citation accuracy. A customer support platform needs reliability on intent classification and tone. Neither benefits from improvements to the model’s ability to prove novel theorems.

Moreover, the relationship between capability and value is S-curved. Early capability improvements unlock entirely new use cases: a model that goes from 40% to 70% accuracy on a task might cross the threshold from “useless” to “useful with human oversight.” But a model that goes from 92% to 96% often delivers no additional value, because the human workflow was already designed around spot-checking outputs and the bottleneck has shifted elsewhere to latency, cost, integration complexity, or user experience.

This is the crux of the argument: once a model clears the capability threshold for a given task, further intelligence improvements face rapidly diminishing returns. The contract analysis tool that’s “good enough” for lawyers to trust with first-pass review doesn’t become twice as valuable when the underlying model gets twice as capable. It just becomes overprovisioned.

II. The Task Saturation Phenomenon

For any specific task, the marginal value of model capability saturates at some threshold. Beyond a certain point, users cannot meaningfully distinguish between a model of size X and a model of size n×X for any n ≥ 1.

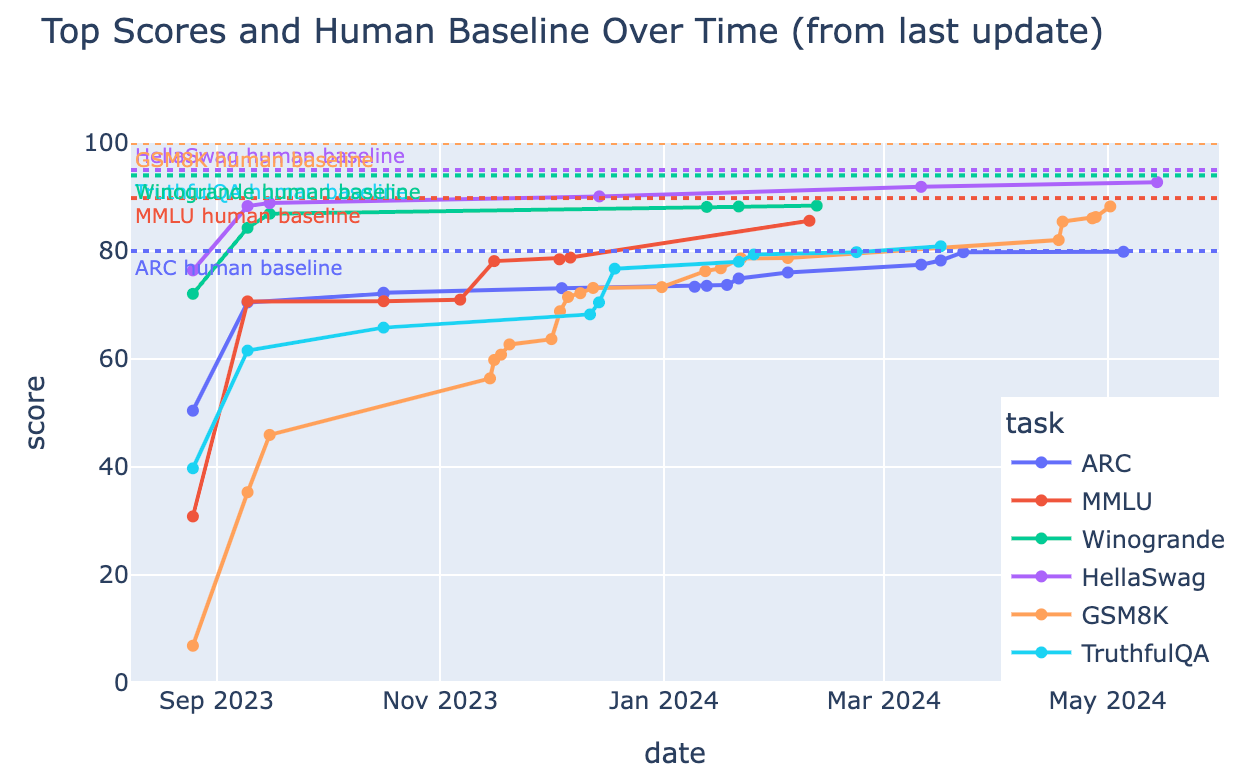

Consider what’s happened to standard benchmarks over the past few years. The chart below tracks top scores on benchmarks like ARC, MMLU, Winograd, HellaSwag, GSM8K, and TruthfulQA against their human baselines:

The pattern is consistent: rapid improvement followed by convergence toward (and often slightly beyond) human-level performance. Once a benchmark is effectively “solved,” additional capability improvements deliver zero marginal value for tasks that benchmark measures. A model scoring 95% on MMLU isn’t twice as useful for MMLU-adjacent tasks as one scoring 90%. For most practical purposes, they’re equivalent.

III. Reframing the Analysis: Cost at Fixed Performance

If capability saturates for specific tasks, then the relevant question isn’t “which model is most capable?” but rather “which model solves my task at the lowest cost?”

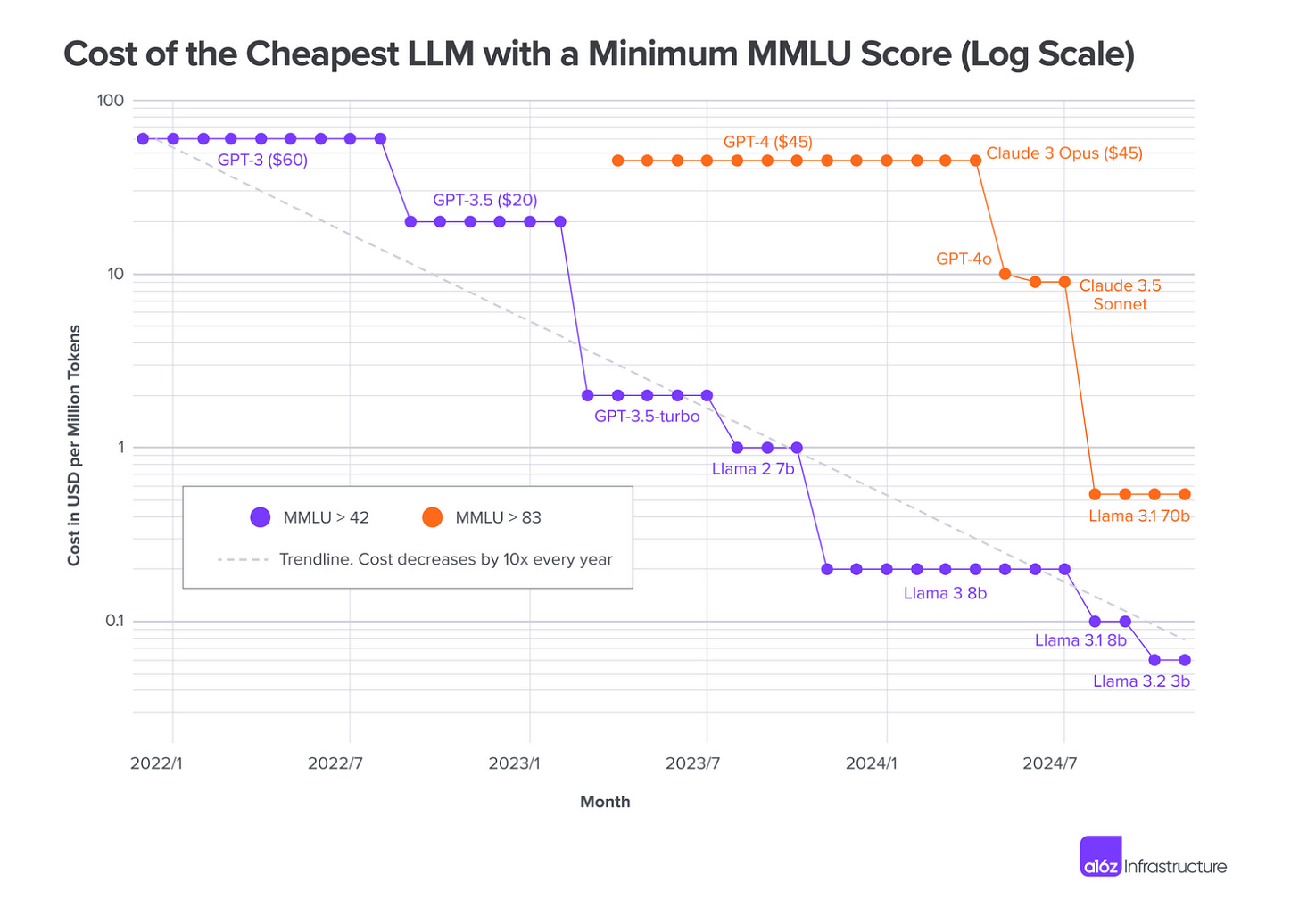

Once we fix a performance threshold (the point at which a task is effectively solved) we can track how the cost to achieve that threshold evolves over time. The a16z team did exactly this analysis for MMLU scores:

The trend line shows roughly a 10× cost reduction every year for a fixed capability level. But the more important pattern is which models sit on that cost frontier over time. Early in a capability tier’s lifecycle, closed-source models from frontier labs define the frontier. But within months, open-source alternatives emerge at dramatically lower price points.

Look at the progression for MMLU > 83: GPT-4 at $45 per million tokens, then GPT-4o at ~$10, then Claude 3.5 Sonnet at ~$10, and finally Llama 3.1 70B pushing costs down toward $0.50. The same pattern plays out for every capability threshold: closed source models solve the task first, and then open source models quickly make it cheaper.

Thus, if we imagine a fixed benchmark score as a proxy for the threshold at which a task is “solved”, we see that closed source models have historically had a payoff horizon of roughly one year before open source models made

IV. Case Study: MMLU Pro Replication Speed

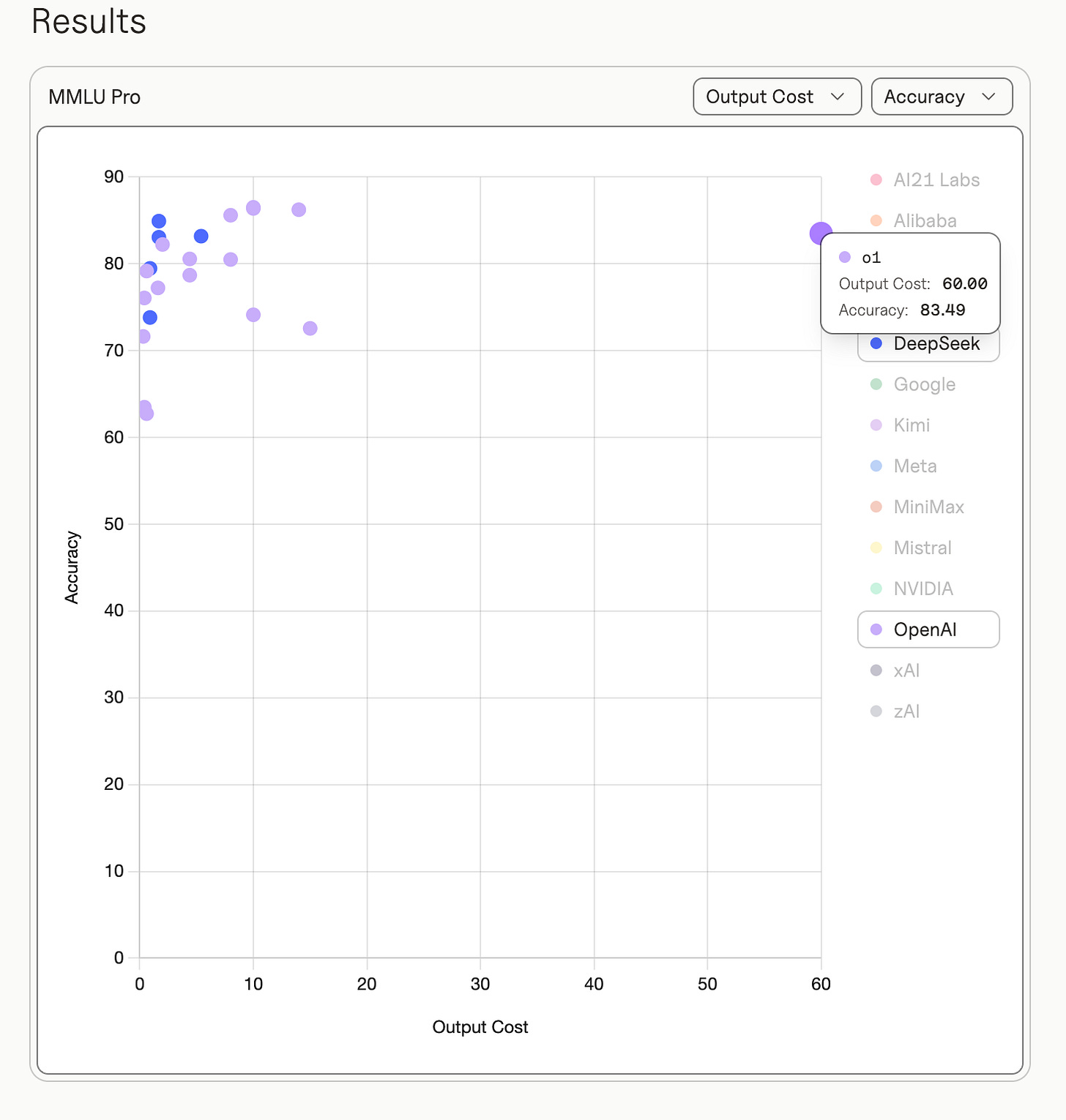

MMLU Pro extends the original MMLU benchmark by increasing multiple choice options from 4 to 10, introducing misleading distractors, and emphasizing reasoning-heavy questions. It’s a harder benchmark, which allows us to separate out the performance levels of recently released models.

Consider the 83% performance threshold. That is, models which answered at least 83% of questions correctly:

OpenAI o1 was the first model to reach this level and did so upon its release on December 5, 2024. Its API pricing was $15 per million input tokens and $60 per million output tokens. The total cost to run the benchmark was $75.

DeepSeek R1 was the first open source model to reach this level when it launched on January 20, 2025, priced at roughly $1.485 per million input tokens and $5.94 per million output tokens. The total cost to run the benchmark was $6.75

That’s an order of magnitude cost reduction in one month for equivalent task performance. If we want to be generous and use the release date of o1-preview, this still results in a time horizon of only 4 months before DeepSeek matched its performance with an open source model costing an order of magnitude less.

To drive the point home further still, DeepSeek V3.2 came out on December 1, 2025 and again achieved the 83% performance threshold, but this time at a two order of magntiude reduction in cost when compared with OpenAI o1. Specifically, the total cost to run the benchmark was only $2.24.

Thus, for a fixed level of performance, we see the price drop from $75 to $6.75 to $2.24 over the course of a single year. As a result, I argue that any task solved by a closed source model will see enterprise buyers transition to cheaper open source models within 6 months to one year.

And there’s reason to expect this pace to accelerate. As Huawei and SMIC close the gap with NVIDIA and TSMC, and now that NVIDIA potentially regains the ability to sell H200 chips in China, the Chinese open-source labs will have access to better hardware while maintaining their cost structure advantages. We may be looking at only a couple of months between closed-source frontier releases and open-source replication with substantial cost reduction.

V. The AGI-Agnostic Conclusion

What I think makes this view most compelling is that it doesn’t depend on AGI being decades away.

The conventional case for open source often rests on an assumption that we’re approaching a capability plateau. That is, that base model improvements will slow down, shifting competition to fine-tuning, cost, and vertical specialization. This assumes that the vision of the future espoused by the US AI labs, predicated on artificial superintelligence (ASI) and runaway intelligence explosions, is wrong, while China’s view of commoditized intelligence is correct. That may well be true, but it’s a bet on a particular trajectory of AI progress.

The task saturation argument is stronger because it’s agnostic to the AGI timeline. When you’re building a company, you’re typically building for a specific use case. That means you’re operating in the saturation regime, not the model scale-up regime. Even if frontier models continue improving rapidly and the AI-2027 timeline plays out, the task your company is built around has a capability threshold beyond which additional model intelligence doesn’t matter.

And once you’re in the saturation regime, the only dimension of competition that matters is cost. Open source wins on cost, systematically and structurally, because open-source economics allow for lower margins and broader distribution.

The practical takeaway for company builders is this: bias toward open source, and do so for cost reasons rather than capability bets.

If you’re building an AI-native product, ask yourself: what capability threshold does my use case actually require? Chances are, that threshold is either already achieved by current open-source models or will be within 6-12 months of a closed-source model first reaching it. Build your infrastructure and workflows around the assumption that you’ll be running on open-source models, even if you start with closed-source APIs for speed to market.

The benchmark that matters isn’t “which model is smartest.” It’s “which model solves my task cheaply enough.” And open source is destined to systematically win that competition through relentless cost deflation.