The US and China are engaged in a two-country race towards an AI-powered future. Both countries have directed funding, policy initiatives, and talent towards the AI sector at levels matched only by the internet buildout of the 1990s or railroad construction of the 1880s. But both of these countries are building towards diametrically opposed futures.

One country has taken the view that it is on the path to artificial superintelligence (ASI) — the point at which AI will be more effective than the most capable humans at every task. The view of their prominent AI labs is that once ASI is achieved, there will be a runaway intelligence explosion, with the AI rapidly improving itself and reaching unthinkable levels of intelligence. This genius AI will then be able to solve our most pressing problems in mathematics, physics, philosophy, and more with minimal difficulty.

The other country has taken the view that it is not peak intelligence that matters, but rather the distribution of intelligence. It aims to develop intelligent AI models (though not superintelligent) that are fast and cheap enough to be embedded in machines across the economy. It wants household robots in every home, talking cars, and refrigerators that can do the grocery shopping.

One future is top-down, the other is bottom-up. One is centralized, the other is decentralized. One results in gains accruing to the select few corporations, the other results in gains throughout the entire economy. One is Skynet, the other is The Jetsons.

The great irony of the current AI race situation is that the centralized SkyNet future belongs to the democratic United States, and the decentralized Jetsons future belongs to authoritarian China.

The Skynet Future

Skynet is the fictional AI developed by Cyberdyne Systems in the original Terminator movie. It’s a large, powerful AI system that, once deployed, rapidly increases its intelligence to the point of becoming self-aware. When it becomes self-aware, it becomes self-interested and decides that the best way to preserve its existence is to eliminate all humans. Skynet then appropriates the nuclear codes of the United States and launches these nuclear weapons in an attempt to eliminate the human race from the face of the Earth. Small groups of humans survive the nuclear fallout, and they live in a post-apocalyptic world fighting robots directed by Skynet that are attempting to exterminate humanity once and for all.

This vision is very apocalyptic, but I think it captures the sentiment of the US AI scene better than any other popular depiction of AI. From the initial ambitions of Skynet running the United States to its intelligence explosion to its final destruction of humanity, these views are not outlandish in Silicon Valley. In fact, they may be the norm among AI researchers and AI lab CEOs. And these views have substantial implications for how AI research is playing out in the United States.

The CEOs of AI research labs are explicitly building towards this form of superintelligence. Crucially, these labs view pushing the intelligence frontier of these models as the core goal of their research. They explicitly look to benchmarks that measure intelligence on extremely difficult tasks (such as FrontierMath, GDPVal, and ARC-AGI-2) as the core metrics that they’re optimizing against. Their goal is to produce a “country of geniuses in a datacenter”, as Dario Amodei put it in his article “Machines of Loving Grace”. Amodei believes that, once achieved, artificial superintelligence could compress 50-100 years of biological research into 5-10 years.

Moreover, many of the prominent figures in AI view the path to superintelligence as a race. They believe that as we move closer to superintelligence, we will be able to achieve an automated AI researcher that can analyze its own codebase and improve it rapidly. These algorithmic gains from AI producing its own code improvements will result in an intelligence explosion, such that the first lab to produce an automated AI researcher will immediately gain an insurmountable lead in intelligence over the other labs. As such, not only do the AI lab leaders believe this Skynet scenario, but they also view it as a race that must be won at all costs. The very existence of their companies in their minds depends upon reaching the superintelligent AI first. To understand the pace of AI investment and the amount of that investment that becomes allocated to training ever-larger and more capable models (rather than more cost-efficient or broadly distributed models), you need to internalize that the prominent figures in AI strongly believe this to be the true state of the world.

To race towards superintelligence, massive increases in the two core inputs to AI training are needed: data and compute. As a result, the AI labs have invested hundreds of billions of dollars into massive compute scale-outs, data acquisitions, and RL environment development. New data centers are coming online that consume gigawatts of electricity to train larger models with higher parameter counts. In addition, these new models are fed data and trained in RL environments produced by hired PhDs and leading experts across math, computer science, finance, and more.

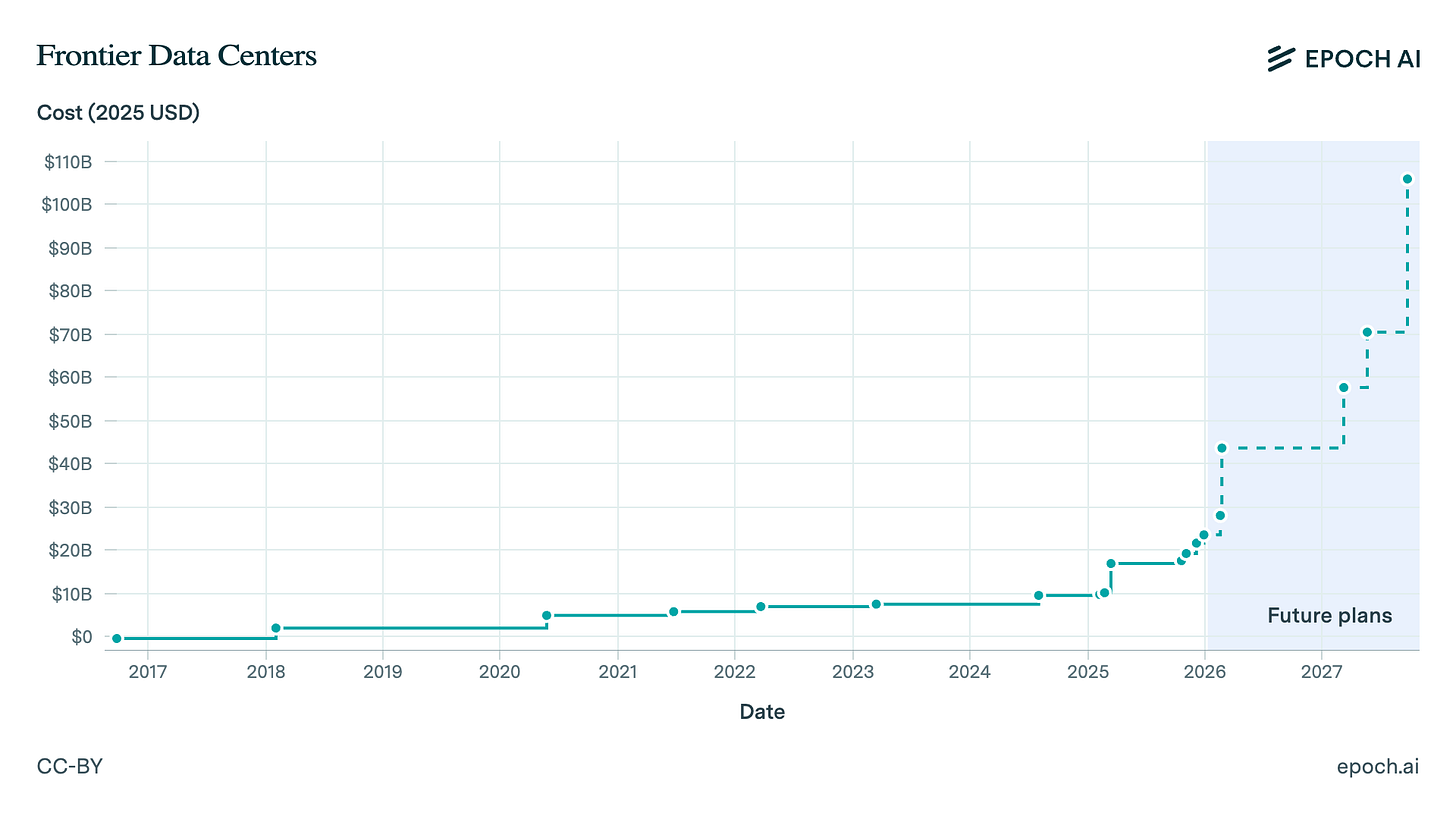

To afford the energy, compute, and data to produce these models that push benchmark metrics on FrontierMath and GDPVal, more and more centralization is encouraged in AI research. As shown in the chart above, the cost of building a frontier data center has been increasing exponentially, from around $7 billion in 2022 (when ChatGPT was first released) to a projected $106 billion in 2027. Hence, if there is a fixed amount of private & public funding available to AI companies, it is in investors’ interest to allocate that funding to a small number of companies so that they can afford the requisite frontier data centers to train these models. With funding too widely distributed, no single player would be able to produce a model that outperformed the state-of-the-art on these frontier benchmarks.

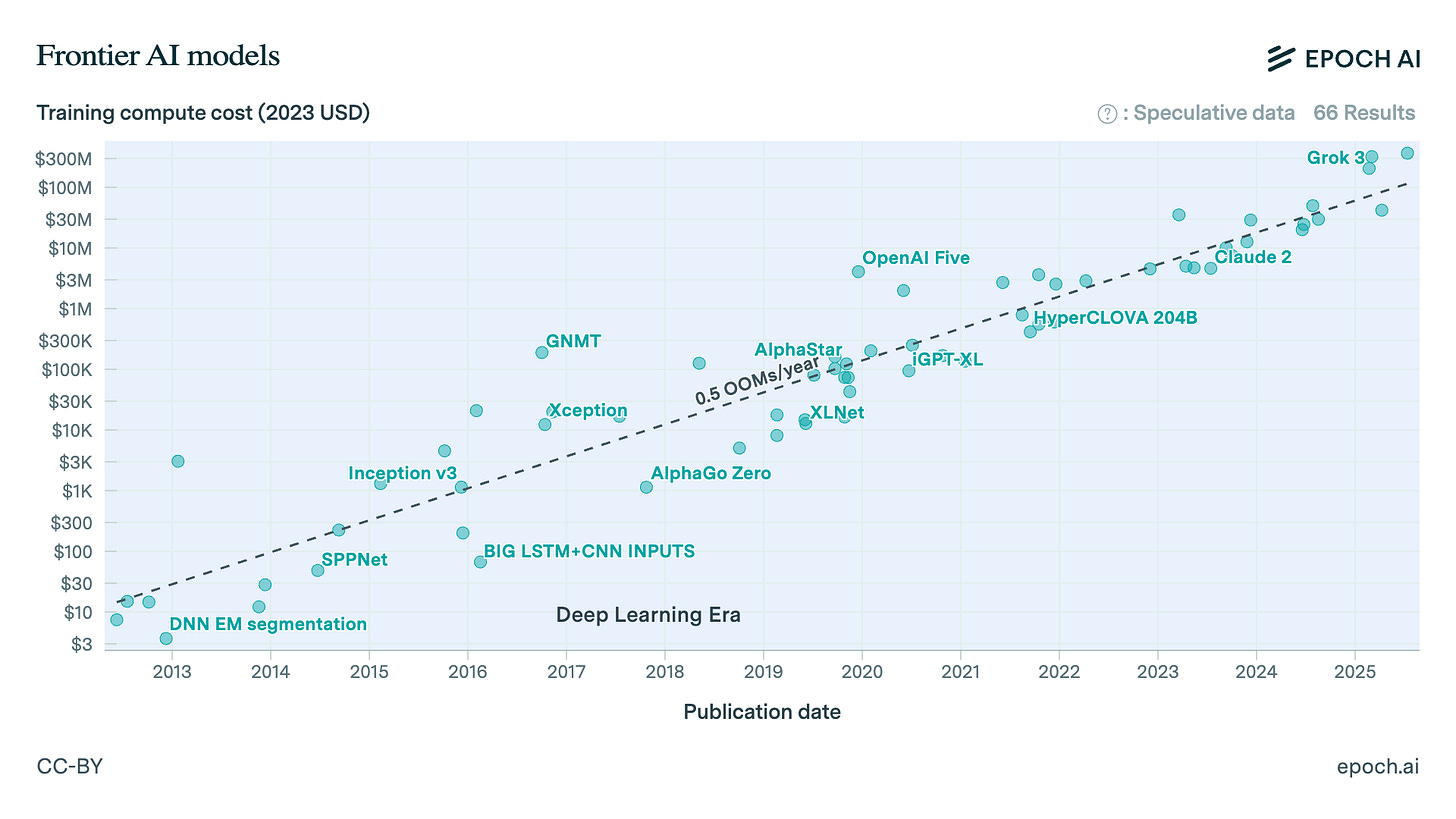

We can observe this trend more clearly in the training compute cost of frontier models from 2012 through 2025. We can see that model training costs rapidly increased from roughly $3 million in 2022 to over $300 million in 2025. In addition, the trend line shows this cost increasing at a rate of 0.5 orders of magnitude per year, indicating that the cost of a single training run next year (2027) will increase to about $3 billion. Projected forward to the end of the decade (2030), a training run would cost roughly $100 billion (with the data centers powering such a run likely costing in excess of $1 trillion).

Given all of this, we can think of the American AI ecosystem as a bet on increasing centralization and increasing scale. It is a bet on a benevolent Skynet future — leveraging unprecedented resources to build a single, massive AI model capable of solving the most difficult problems in science, technology, politics, and philosophy.

The Jetsons Future

The Jetsons is an animated sitcom from the 1960s that depicts a future defined not by a single technological breakthrough but by the accumulation of countless small conveniences — flying cars, household robots, and apartments that predict each family’s needs. The Jetsons’ future is not one of transcendence but of leisure — technology has not produced a godlike intelligence but has instead seeped into every object, automating away the drudgery of daily life. The show’s vision is one of abundance through distribution: no single machine is particularly impressive, but the sheer proliferation of helpful machines has transformed the nature of work and home life entirely.

The Jetsons aired the same year as the Cuban Missile Crisis. Sixty years later, it is the CCP & China, not the United States, that is building toward its vision.

Chinese AI labs burst onto the scene in early 2025 with the release of DeepSeek-R1. Unlike its American counterparts, the notable aspect of DeepSeek’s model was not its raw performance — it was strong, but it lagged behind the frontier. The truly impressive aspect of DeepSeek-R1 was that it performed similarly to frontier models at a fraction of the cost, both in terms of serving cost and training cost. For example, as I detailed in another article (Open Source LLMs Are Eating the World), DeepSeek-R1 was able to perform nearly as well as OpenAI o1 (the frontier model at the time) on the MMLU Pro benchmark, while only costing $6.75 to run the full benchmark suite compared to o1’s $75. This represented an 11x drop in the cost to serve the model at roughly equivalent performance levels.

The success of DeepSeek-R1 has sparked a wave of innovation in open-source Chinese AI. Various companies have entered the fray, including Alibaba with its Qwen series, Z.ai with its GLM series, and Moonshot AI with its Kimi series. Each of these three core competitors, along with DeepSeek, has steadily pushed the cost of economically useful intelligence towards zero.

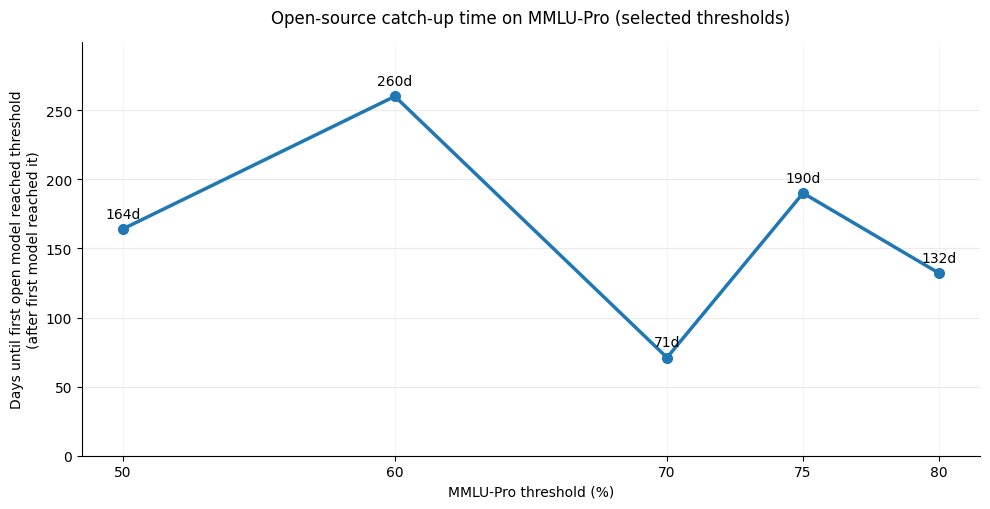

In addition, the speed of innovation has compressed the time delta in model performance between closed-source AI labs and their Chinese open-source equivalents. The chart above shows the catch-up time required for open-source AI models to match the performance of closed-source models at different performance thresholds on the MMLU-Pro benchmark. We can see that earlier performance levels, such as the 60% threshold, required roughly two-thirds of a year before open-source AI could match closed-source AI. However, recent performance thresholds have been achieved in far less time, between a quarter to a third of a year. Chinese AI labs have ramped up their investments in data centers and energy. They now have access to purchase NVIDIA H200 chips, and the Chinese chip ecosystem is maturing more quickly than expected. As a result, we should likely expect this time gap to continue to compress rather than to expand.

The implications here are genuinely massive. This chart shows that open-source AI models from China can match the performance of our leading closed-source models in less than 6 months, often at an order of magnitude lower cost.

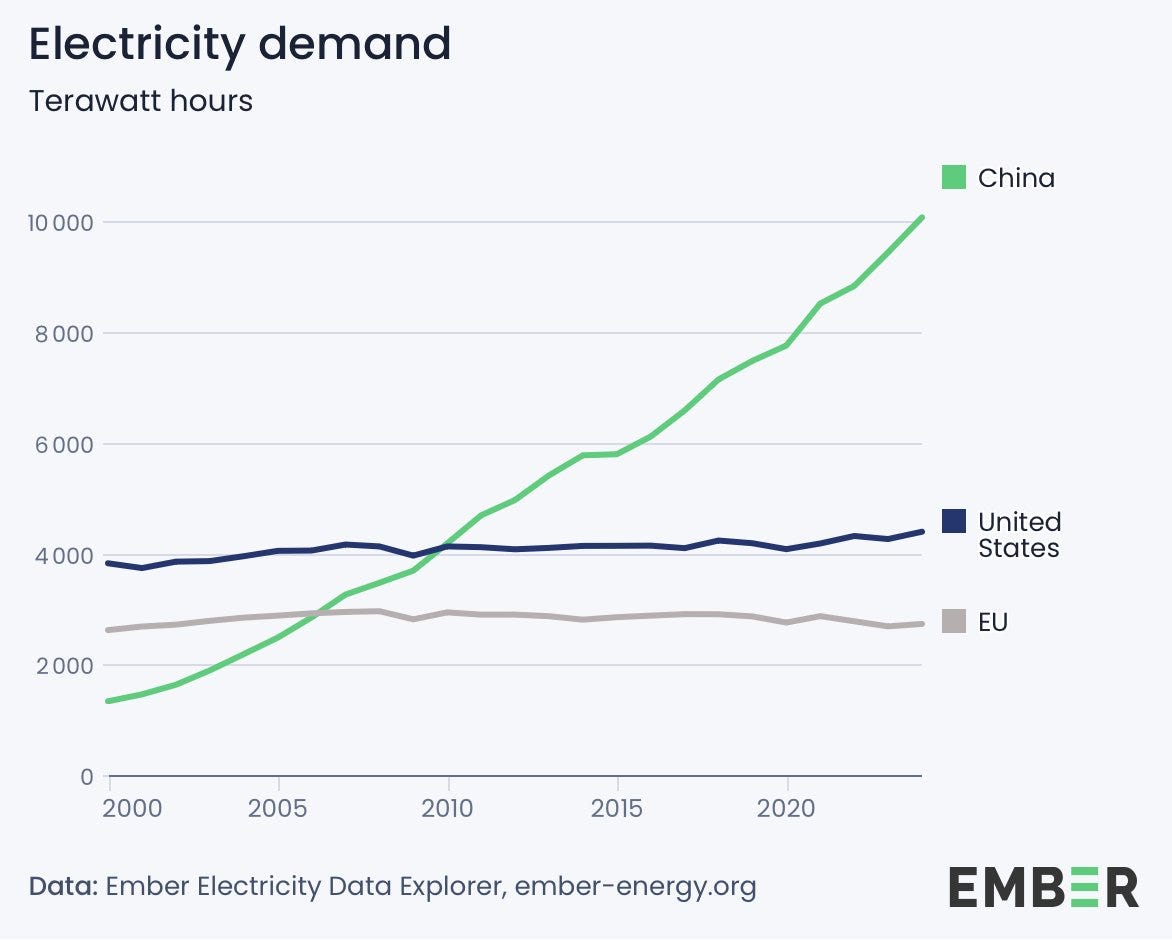

In parallel with these advancements in open-source AI, China has been experiencing two massive buildouts over the last five years. The first has been a huge increase in energy generation, specifically in solar and nuclear energy. These rapid increases in energy generation, which frequently exceed the rest of the world combined, for example, in installed solar capacity, are enabling manufacturing at scales never before seen. In particular, the improvements to solar and batteries that are occurring and will continue to occur due to technological and cost improvements driven by this increased manufacturing will allow energy not just to be more plentiful overall, but also to be more local to specific needs. What this means practically is that energy will become local and mobile, allowing for various devices to become much more energy-intensive than they have been previously through the use of improved batteries and local solar panels. This will allow devices to include the substantial onboard compute required to run the top open-source AI models.

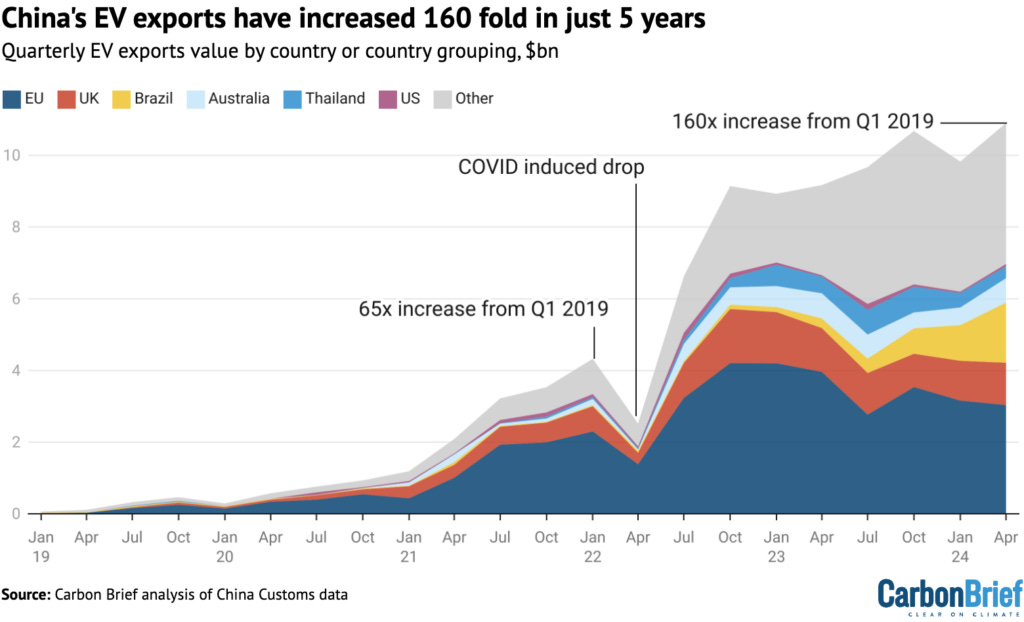

The second key build-out has been in advanced manufacturing. China was already the world's manufacturing center before this push into advanced manufacturing. But now it has moved up the value chain and very quickly has gone from a laggard in key industries to dominating them. For instance, five years ago, China was largely irrelevant in the electric car market. Now its electric car companies are leading the world and outselling Tesla. Several leading companies are now making strong pushes into humanoid robots and are setting the pace in that category.

This confluence of advanced manufacturing in robotics & battery-powered vehicles, increased energy generation (specifically solar), and open-source AI that is energy- and compute-efficient will allow China to develop a truly intelligence-powered economy. The major factors will be in place to have human-level AI embedded into a large share of both consumer and industrial products.

With this approach, China aims to enable a new level of general abundance with household robots, self-driving electric cars, self-directed delivery drones, and household appliances that can make decisions for themselves, such as a refrigerator that can detect when you’re running low on specific supplies and order them agentically.

And crucially, this future does not depend on reaching superintelligence. As I’ve detailed in my other article, Open Source LLMs Are Eating the World, many economically relevant tasks operate in a task-saturation regime. That is, once the models exceed some threshold level of performance, future increases in model scale and training compute do not make meaningful differences in task-level performance. Moreover, models today are already capable of performing many economically viable tasks, such as coding complex apps, serving as customer support agents, and more. Hence, this broad deployment of cheap AI in physical goods will deliver returns quite quickly.

Making this intelligence cheap and abundant through energy- and compute-efficient open source AI will unlock massive economic value across the spectrum. There isn’t much doubt about this. The Jetsons future is clearly within reach. However, there is a question mark whether we will reach the benevolent Skynet future.

Consequences of the Divide

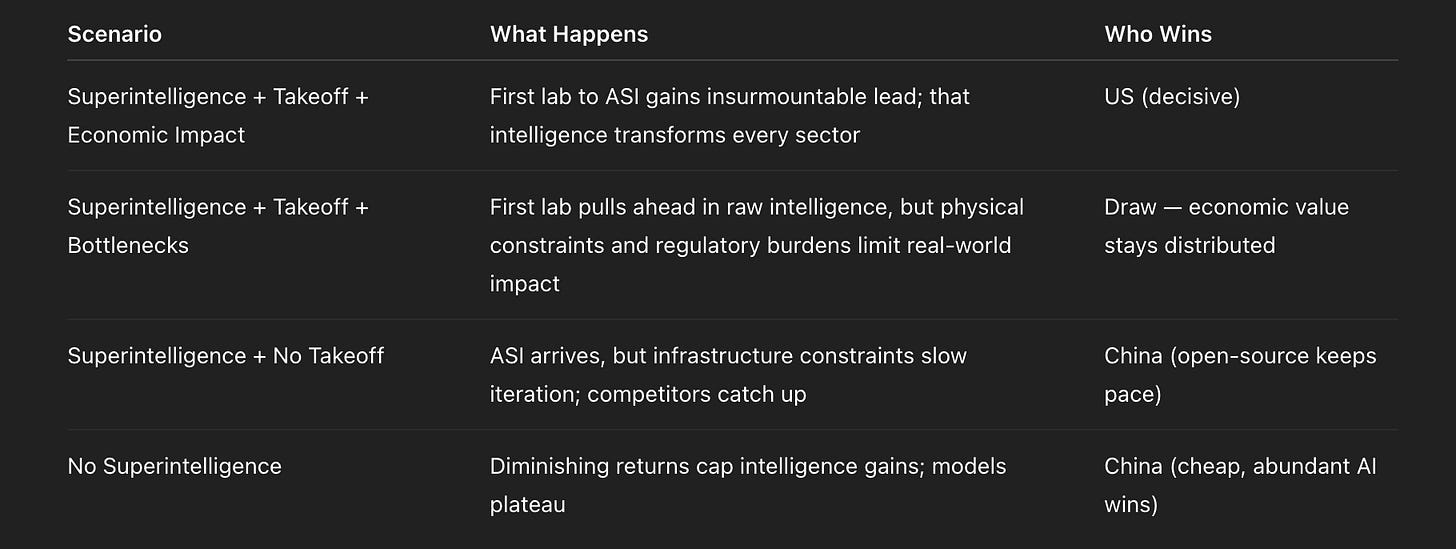

US labs are betting on transcendent intelligence. Chinese labs are betting on abundant intelligence. Who wins depends on which future actually arrives.

Four scenarios are possible. Only one favors the American approach.

The Scenario Matrix

From the above matrix, we see that the American bet requires threading a needle: superintelligence must be achievable, it must trigger a runaway intelligence explosion, and that explosion must translate into massive economic returns unconstrained by physical bottlenecks.

Remove any link in that chain, and the calculus shifts.

If superintelligence arrives but can’t escape physical constraints: The leading lab pulls ahead on benchmarks, but drug discovery still bottlenecks at FDA trials. Robotics still bottlenecks at manufacturing. Most economically useful tasks don’t require superintelligence anyway. Open-source competitors deliver similar real-world value at a fraction of the cost.

If superintelligence arrives but no takeoff occurs: Energy infrastructure takes years to build. Training runs take months. Even with a superintelligent AI optimizing your codebase, the results manifest slowly enough for competitors to close the gap. No insurmountable lead materializes.

If superintelligence never arrives: Intelligence gains follow a sigmoid curve—rapid improvement, then diminishing returns. At that plateau, the race shifts from “who’s smartest” to “who’s cheapest and most distributed.” China wins that race.

The Asymmetric Bet

The Jetsons future requires no miracles. Cheap, capable AI embedded in robots, vehicles, and appliances delivers value whether or not superintelligence is possible. China’s bet pays off in three of four scenarios.

The Skynet future requires everything to go right. Superintelligence must be reachable, takeoff must occur, and physical constraints must not bind. America’s bet pays off in one scenario.

The Implication

We see from the scenarios enumerated above that the US AI Lab approach is decisively dominant in only one of them. In all other scenarios, Chinese open-source AI is able to keep pace with the closed-source frontier, and, in doing so, it is guaranteed to bring about the Jetsons future that China is building towards. The American benevolent Skynet future is far from guaranteed.

In sum, to ensure that the United States broadly benefits from the AI revolution it has itself started, we need to take a page from the Chinese AI playbook. We must ensure that even if superintelligence is out of reach, we will have cheap, abundant intelligence suffused throughout the economy. We must ensure that our portable energy infrastructure (i.e., solar panels and batteries), our robotics manufacturing capabilities, and our open source AI efforts are sufficient to power a truly intelligent economy. The failure to do so may cede technological leadership in the 21st century to the CCP & China.

Great post! This (and the previous open source one) have been quite eye-opening for me.

I note that the scenario matrix is missing a rather important causal link - that superintelligence is and remains benevolent :)